Quality beats quantity: Quentin King on fine art and screen printing

Quentin King, the founder of Newhaven-based fine art printer Harwood King, on how he achieves consistent results in a highly demanding sector.

In the exacting world of fine art printing, there is no room for error. “The most important thing for us is quality,” says Quentin King. “Most manufacturers talk about how much machines can produce in an hour. But for us, it’s about determining how fast a machine can produce the best possible quality.”

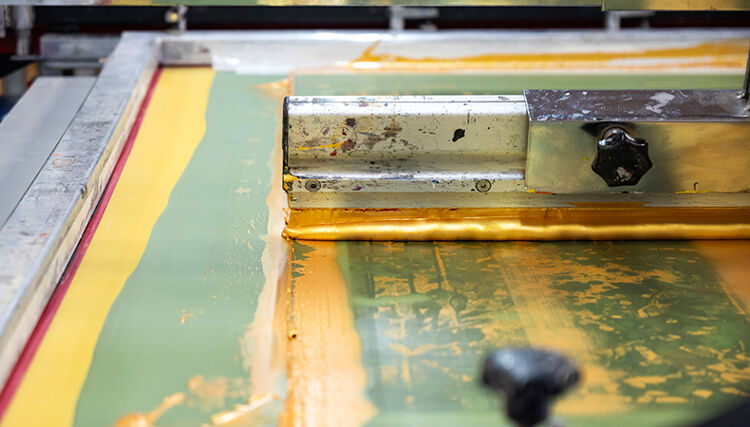

One reason for Harwood King’s success is the fact that it does things a little differently. Quentin pioneered the use of combination or hybrid printing – mixing new technology with traditional silk screen printing – which has proven particularly useful in satisfying the creative demands of the fine art world.

“Initially, way before others we produced giclées with silk screen colour and varnishes printed over the top. That was very successful,” Quentin says.

In fact, Harwood King’s ability to produce extremely high-quality prints was so successful, the business developed an enviable reputation among galleries and artists worldwide.

Fine details

However, Harwood King’s beginnings were more humble. “I studied graphics and design at college, but I was always interested in screen printing. I took a job printmaking with a London studio but soon decided to set up a little studio in my flat in Brighton, using my bathroom to wash out screens and my living room to make prints,” Quentin says.

“My brother and I worked together creating our own editions, which was the beginning of the business. I produced my own prints for many years, but then other artists asked me to produce theirs. Over the years, the company has grown. My son Caspar has joined me – he is now the Managing Director and will take the company forward, with new departments and ideas. Caspar has already revolutionised our marketing and social media presents as well as implementing an MIS [management information system] to track production and planning. We are building the business for a second generation.”

Standards are far higher in the fine art world, Quentin says. “I’ve noticed that, when supplying commercial work with no blemishes on the print, customers can be surprised, but in the fine art world, if you give a client a print with a blemish, it is immediately rejected – it is lost money. We have to run 20% over to get the correct number at the end of the job. That is a very high percentage but it’s because any mark created by any part of the production process is rejected.

“That makes it expensive and slow. It requires massive quality control and a lot of attention to detail. We have to spend a significant amount of time training people to get them to understand what is needed.”

Finding the flatbed

While Quentin continued to use inkjets for a while, he was simultaneously looking at the prospect of using flatbed printers with the hopes of improving quality.

“I could see there were definite advantages with flatbeds because they are dimensionally accurate,” Quentin says.

“Eventually we bought a Canon flatbed – there was quite a discussion among my family about whether this was the right decision. I was enthusiastic that the flatbed had numerous benefits and, eventually, I got my way. We installed the flatbed only to discover that the things that I thought it could do for us, it didn’t do very well. However, it did offer the opportunity to create other printing techniques and greatly shortened production time.”

Harwood King’s first flatbed might not have performed as well as Quentin had anticipated, but it was a huge success nonetheless and within two years the company had acquired a second machine. The first flatbed was then replaced with a more modern alternative, and now, Quentin says they are looking at purchasing at faster and bigger flatbeds.

“The flatbed will print an image onto almost any substrate, as long as the substrate has a completely flat surface, down to the millimetre. We measure the thickness of the material with a micrometre before we put it onto the bed. Acrylic, glass, paper, canvas – any of these will work very well,” he says.

“One of the significant advantages is that the printed image will be dimensionally perfect in size. With a giclée machine or a roll-to-roll inkjet machine, it’s not perfect and, therefore, is very hard to register, which causes problems post-processing, such as adding gold leaf, diamond dust, fluorescent colours or silk screening areas.

“We also do a lot of jobs where we will initially silk screen a texture, then we’ll move to the flatbed for the image to be printed, and then return the print to the screen press for extra varnishes or embellishments. We also produce images where we will screen print on glue, add a gold leaf, and then flatbed an image on top of the gold leaf. Then, it might go back to the silk screen department to have some varnishes added. Therefore, a print can go to and from the studio for additional processes, each creating a different look.”

Colour perfection

Those embellishments, such as gold leaf or diamond dust, are some of Harwood King’s most striking examples of silk screen. However, on fine art products where colour replication is absolutely vital, silk screen also allows Quentin and his team to match the artist’s colour choice perfectly.

“Flatbeds are limited mostly to CMYK, and CMYK can only produce around 50% of the visual spectrum,” Quentin says.

“Artists tend to use very vibrant and very saturated colours – they usually mix pure pigments for their paintings. There are many colours that they will paint with, which will be out of the gamut for a CMYK printing process. For example, CMYK reds tend to be a bit weak and deep ultramarine is pretty much impossible to print. Therefore, we must go to a silk screen press to put those out-of-gamut colours on.

“It’s particularly relevant with deep, dark colours. To produce these using a CMYK colour mix, black needs to be part of the mix. But by using only the pure pigments, you can print a deep rich colour with far more intensity. An intense ultramarine can be obtained using a screen overprinting an area five or six times using translucent layers over the top of each other. By doing this, you get an incredibly deep dark and vibrant ultramarine that you could not achieve in any way single printing with CMYK.

“We also add fluorescents to colours in varying quantities should we need to lift a colour. It is important to be careful as fluorescents don’t have a long life, although they seem to last much longer when mixed with other pigments.”

Long time coming

With such attention to detail, Harwood King’s workflow doesn’t match a typical commercial printer’s ‘print them and ship them’ approach, with some projects taking months or even years to complete.

“There are usually four different projects happening at the same time in the studio, and some of these projects can take a long time. We have just finished one, which we discussed with our client last Christmas, we started work in August 2023, and we’ve literally just shipped the first ones out the door. We’re now working on a canvas project that has been two years in the making. First proofed two years ago, we have been making progress on it,” Quentin says.

“Some artists just want you to do what they want, and that’s fine but we discuss the process with them. One crucial thing we bear in mind is to manage a customer’s expectations. Sometimes, an artist has artwork that they need to be screen printed. We have to tell them that it could be challenging to register or we might need to use 20 colours, after which it still wouldn’t look like the original.

“A 100% silk screen, using 20 colours, will look fantastic but we can achieve a similar result with just two or three silk screen colours on top of a flatbed print. The price difference and the time difference are significant: hybrid printing is very cost-effective. That means the artist gets more profit, gets the product quicker, and they can sell it for less if they want to. It gives them options, and it’s not a lesser product.

“People sometimes think everything has to be done by hand, but a 100% screen print might not look as perfect as a combination print. A perfect screen print is a slow and considered process that requires time without any pressure. It’s no good saying you need it next week – the screen print will take the time it needs. We can do a exceptional job by using the flatbed and then adding screen colours over the top. It looks fantastic.”

For more information on Quentin’s work, see harwoodking.com

Become a FESPA member to continue reading

To read more and access exclusive content on the Club FESPA portal, please contact your Local Association. If you are not a current member, please enquire here. If there is no FESPA Association in your country, you can join FESPA Direct. Once you become a FESPA member, you can gain access to the Club FESPA Portal.

Topics

Recent news

Regulation guidance: Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) is now in effect, but with further changes on the horizon, what does it mean for printers? Sustainability consultant Rachel England outlines everything you need to know and talks to Apigraf about how your business may be affected.

Web-to-print design: Canva versus Kittl

We look at popular design packages Canva and Kittl to determine how they compare regarding graphic design and print on demand.

FESPA in South Africa: the print skills to thrive

Printing SA’s Career Day inspired young Cape Town learners to explore printing and packaging careers.

The rise of Chinese printers

Chinese printing companies are on the rise, and have their eyes set on the UK and EU marketplace. Some have made an instant impact; others are running into issues with maintenance and language barriers. What does the future hold for Chinese printing firms, and how can you navigate working with them?